The Brutalist | The Screenplay Lab

Is success worth it if it requires you to surrender everything that makes you who you are?

The Screenplay Lab is a weekly podcast where we take one screenplay, break it down, and discover what is unique about the literary piece. I’m Jeff Barker, a screenwriter, and I am passionate about screenplays. This is a place where we appreciate their standalone beauty. This week, we do a deep dive into:

The Brutalist by Brady Corbet and Mona Fastvold

THE BRUTALIST

This screenplay is an intense period drama with layered narrative styles. It highlights the struggle to rebuild after a personal and cultural trauma and the promise vs. reality of the American dream.

Is success worth it if it requires you to surrender everything that makes you who you are?

Awards

It has become one of the most talked about and controversial films of the year, nominated for 10 Academy Awards, including:

Best Picture

Best Director - Brady Corbet

Best Actor - Adrien Brody

Best Supporting Actress - Felecity Jones

Best Supporting Actor - Guy Pearce

Best Cinematography - Lol Crawley

Best Film Editing - David Jansco

Best Original Score - Daniel Blumberg

Best Production Design

and what we care most about… Best Original Screenplay (Corbet/Fastvold)

It has already won Best Picture, Best Actor, and Best Director at the Golden Globes.

AI Controversy

Hollywood is grappling with what to do about AI. It is a struggle to protect creatives while at the same time putting up guardrails for a force so gravitational that avoidance is no longer an option.

The Brutalist is at the center of this debate because its creators chose to incorporate AI in the film’s production.

AI was used to refine the characters’ speech to sound more authentic as Hungarian immigrants and to refine some of the film’s architecture.

That’s all I’ll say on this matter, since I am concerned with Corbet and Fastvold’s writing.

Brady Corbet & Mona Fastvold

Brady Corbet and Mona Fastvold are creative and life partners. They have been in a relationship since 2014 and have a daughter. They combine to write intense screenplays that center around historical/psychological themes with societal impacts.

Corbet (36) is from Arizona and began as a child actor before transitioning into filmmaking. He had a role on The King of Queens and many indie films.

Fastvold (38) is from Norway. She also began as an actress, then wrote and directed The World to Come (2020) independently of her partner.

As a team they have co-written:

The Sleepwalker (2014) - Fastvold directed.

The Childhood of a Leader (2015) - Corbet directed.

Vox Lux (2018) - Corbet directed.

The Brutalist (2024) - Corbet directed.

How The Brutalist Was Developed

Corbet and Fastvold spent seven years developing this film. The script demanded extensive research and planning, particularly to capture the historical, architectural, and cultural aspects of America after WWII.

Collaboration began early. Not only did they bring in cinematographer Lol Crawly, but they also enlisted the help of composer Dainel Blumberg during production. They believed the score was a fundamental part of the story’s identity. You can see this in the screenplay, as music is imbedded as part of the DNA.

Eleven production companies got involved at different times during production. Here are a few:

Andrew Lauren Productions - The Squid and the Whale

Brookstreet Pictures - Brothers by Blood

Three Six Zero - Vox Lux

Killer Films - Carol.

The film operated on a tight $10 million budget and was shot in an astonishing 33 days (a fantastic accomplishment for the scope and scale of this movie).

The film premiered at the Venice Film Festival, where it generated immediate buzz. A24 then acquired it for distribution, putting it on track for being one of the most anticipated films of the year.

I Have Not Seen the Film

If you’re new here, you’re probably like… what?

I’m not a film critic; this isn’t a film review. It’s a deep dive into the screenplay. The film I see is the one in my mind based on the words on the page.

But I will watch it soon. I can’t wait.

Logline

The official logline of The Brutalist is:

"When a visionary architect and his wife flee Europe to rebuild their legacy and witness the birth of modern America, their lives are changed forever by a mysterious and wealthy client."

Here is my go at it:

Fleeing post-war Europe in pursuit of the American Dream, a visionary architect wrestles with identity and trauma as he battles with a mysterious patron to bring his artistry to life.

Statistics

Pages - 130

Scenes - 165

Screentime per page - 1:38

This is one of the longest films in recent history, at 3 hours and 35 minutes (including a 5-minute intermission). If this screenplay had followed your professor's 1 minute per page rule, it would have been 210 pages.

Quentin Tarantino’s The Hateful Eight (Roadshow Edition), released in 2015, was the last major Hollywood film to incorporate an intermission.

The Title’s Meaning

I have found four meanings for the title of this project, with each one going a layer deeper. We’ll start with the obvious:

Architectural Style

Brutalist architecture emerged after WWII as a raw, blunted, functional style that was practical, cheap, and fast to construct. Some saw this as a socialist utopia, others viewed it as cold and oppressive. This mirrors the screenplay’s conflict between artistic vision and harsh reality, idealism vs. pragmatism.

Uncompromising Personality

The protagonist, Laszlo, embodies Brutalism. He is unyielding, stark, unapologetic, and committed to his vision. His dedication to his artistry and identity makes him a polarizing figure. People react to him with anger and jealousy, resenting his refusal to conform. His rigid sense of self and commitment to his work create concrete walls, even between those he loves.

Post-War Survival

At its core, this is a story about the brutality of starting over. For immigrants and refugees, rebuilding life in a new country is often marked by physical and psychological pain. The struggle is more than survival. It’s about fitting into a society that doesn’t fully accept you. The screenplay doesn’t shy away from the sacrifices and moral compromises necessary to assimilate.

The American Dream

This story is about the erosion of idealism—the American Dream vs. the American Reality. The reality can be brutalizing. Success may be possible for anyone, but the starting line and obstacles are not the same.

Formatting, Mechanics, and Style

Chapters

The script is divided into distinct chapters, each marked by unique font and text size. This gives the screenplay a very organized texture, similar to Brutalist architecture.

pg. 1 - OVERTURE

pg. 4 - PART ONE: The Enigma of Arrival

pg. 68 - PART TWO: The Hard Core of Beauty

pg. 127 - EPILOGUE

Thick Dialogue

The screenplay often presents thick, weighty dialogue sections, reflecting the intellectual nature of the conversations.

This is counterbalanced with short, punchy action lines, keeping the story progressing forward. Like our main character, Laszlo, dialogue carries weight, but action speaks louder.

Again, the document symbolizes Brutalist art with its sturdy, thick foundations.

Montages

The script frequently uses montages (or series of shots). Some are more traditional montage elements used to show the passage of time, while others are more thematic elements used to establish a location or speed up a scene.

This happens eight times (way more than you would see in a traditional screenplay).

Carbet and Fastvold label them “A Series of Angles.” This builds on the story’s architectural themes and the architecture of building this film.

Laszlo’s experience on the ship

Establishing Philidelphia

Laszlo at work

Laszlo preparing Van Buren’s study

Laszlo building an architectural model

Gathering of materials from around the world

Looking for Van Buren

Establishing Venice

Voice-Overs

The screenplay incorporates five voice-overs, all from the voice of someone who has written a letter. The writers use written communication to track time, distance, and emotional shifts.

Several of them are layered over the monologs mentioned above.

Erzsebet’s letter to Laszlo - revealing she is alive

Laszlo’s letter to Erzsebet - revealing his new address

Laszlo’s letter to Erzsebet - revealing she can come to America

Erzsebet’s letter to Laszlo - revealing she has a photograph

Erzsebet’s letter to Zsofia - revealing her frustration with Laszlo

They drive the narrative forward, reveal emotional states, and mark the passing of time. The final one is a crucial turning point of the story, illustrating how obsessed Laszlo has become with his work.

Character Names and Introductions

The screenplay is particular about character names in the action lines. The first time anyone is mentioned, they are not only in ALL-CAPS, but also in BOLD. This allows them to take it a step further and place names in all-caps every time they are mentioned in the screenplay.

The script continues with its no-frills minimalist approach regarding character introductions. This economy of words mimics the Brutalism aesthetic.

Sound and Music Cues

One of the screenplay’s most rigid aspects is the format of sound effects and music. They lay out the document like an organized blueprint, playing on the brutalist theme - precision, intention, obvious, blunt.

All screenplays draw attention to sound design, but it is often incorporated into the action lines as part of the story. Here, they use SFX (7 times) and CUE (18 times).

Transitions

Continuing with the prescriptive brutalist theme, the writers don’t shy away from specific transitions.

Jump Cut To - 2 times

Hard Cut To - 1 time

Fade To - 6 times

Cross Dissolve - 6 times

Post-Credit Sequence

The screenplay even includes a detailed post-credit sequence. I see this more frequently these days, but it’s still uncommon.

The writers leave the reader/viewers with an emotional look at what was lost and what was built in its place.

Direction on the Page

Practical, prescriptive, unapologetic - the Brutalist aesthetic continues with this screenplay. The writers lay out the cinematography like a blueprint.

Framing

The camera positioning and framing are prescribed a remarkable 95 times.

Close, Close On, Ultra-Close - 15 times

Wide, Ultra-Wide - 10 times

Low Angle, New Angle - 28 times

Tracking Shot - 19 times

Slow Pan, Pan Up, Pan Across, Pan Down, Whip-Pan - 11 times

Bird’s-Eye View - 4 times

POV - 2 times

Lenses

The script even dictates what specific lenses should be used, a rarity in screenwriting, but essential in maintaining the rigid structure of this brutalist document they have created.

Ultra-Bowed Lens - 2 times

Long Lens - 10 times

Wide-Angle Lens - 1 time

Steadicam - 4 times

Handheld - 7 times

Tracking Shot

My favorite direction on the page is this unique five-page tracking shot. I look forward to viewing the film to see if this ambitious movement made it into the movie as described on the page.

This begins on page 121 and goes to 126, when Erzsebet arrives at the Van Buren Estate to confront the antagonist.

Filming and Editing Notes

Technical direction also makes its way into the prose in a very particular way. I appreciate the specificity of these lines. I have seen a lot of screenwriters attempt to describe these shots before. Sometimes it lands, other times it doesn’t. But I don’t think I have ever read anyone describe it so bluntly.

The Writing

Worthy of an Oscar-Nomination

I firmly believe that The Brutalist is worthy of an Oscar nomination for Best Original Screenplay, not just because of its rich storytelling but because the script itself is a piece of Brutalist art.

It is raw, blunt, and as brutal as concrete. The dialogue is massive, block-like, imposing. It’s structured like the buildings Laszlo constructs. The screenplay embraces repetition through mirrored language, recurring voiceovers, and repeated shot compositions, creating a distinct storytelling pattern.

The script is practical, with detailed camera directions, calling for specific lenses and edits, reinforcing the notion of function over ornamentation. Its descriptions are minimalist, stripping away unnecessary embellishment in favor of a clean, unfiltered blueprint.

Like brutalist architecture, it is polarizing, given its take on the American Dream. The screenplay demands the reader to concentrate and get through large blocks of philosophical text. In the end, it is well worth it.

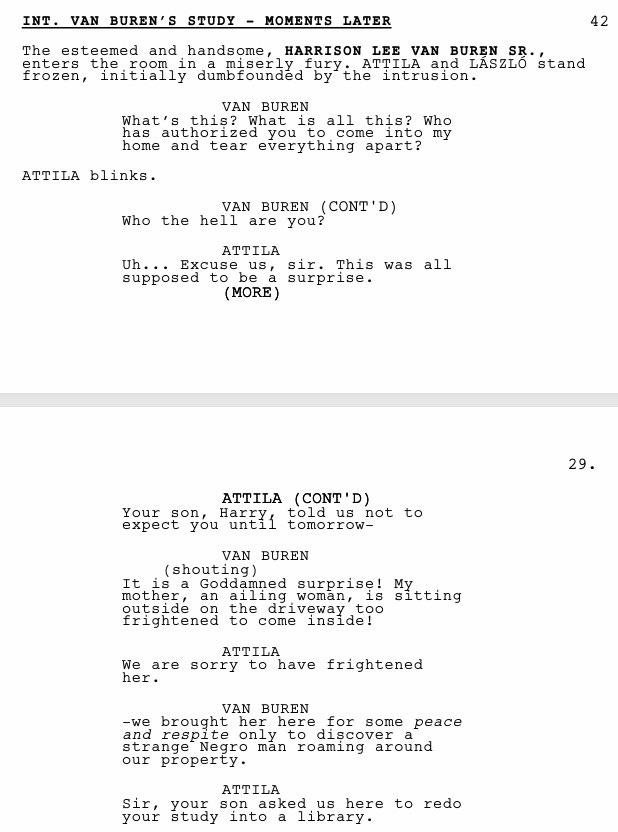

Drawing an Antagonist

The story gives us the antagonist for the first time, turned up to a seven out of ten. This is a good lesson on letting readers know who they are dealing with. Yes, slow burn character development is my jam, but I appreciate how obvious Van Buren is when he creeps onto the scene.

Later, his fake kindness and generosity allow us to be lulled to sleep. Then when he turns the evil up to a ten (assaulting Laszlo), we can believe it. Oh yeah, that’s right, this guy is a horrible person. Consider this character grounded.

Van Buren reminds us of the evil that can be associated with power and privilege. But don’t let that tropey cliche fool you, this protagonist is deeper than that.

He’s a walking contradiction. Van Buren is generous, but only when it serves him. He’s compassionate, but only in the form of a transaction. He’s insecure and jealous. His envy centers on Lazlo—not his talent but his unyielding sense of self.

In the end, Van Buren shows us he is a coward, fleeing the moment he is confronted about the horrors of his actions.

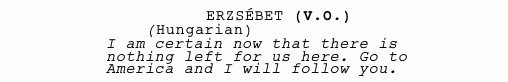

Erzsebet’s Agency

The character of Erzsebet is a ghost for the first third of the script, only arriving in voice-over letters.

Then when she makes her appearance, she is not what we expect—frail, weak, in a wheelchair. This makes us underestimate her and see her as someone who needs to be cared for. That turns out to not be the case.

She is the character gifted with the most agency. She goes to Van Buren’s estate and confronts the antagonist—not Laszlo. She is the one who makes the decision to move to Israel.

The mirrored language of her arc is beautiful.

From this:

To this:

Final Lines

The final lines of the screenplay take place during the Epilogue in 1980. Laszlo is now quite elderly and unable to speak. His niece, Zsofia, whom he used to talk for is now speaking for him.

They are at a ceremony to honor his life’s work.

She is giving us the point of the screenplay. Laszlo has lived uncompromised the second half of his life, after he surrendered the American Dream and moved back to Europe. America was not the saving destination he had hoped.

There, it was impossible to continue to be authentic to himself and honor his ideas/art without giving away a large chunk of himself. For him, the journey wasn’t worth it.

Art can be a painful labor. The journey is a necessary process, but it is not the point. The art is the point.

✅ TikTok

✅ Bluesky

✅ Threads

✅ X

Appreciate this in-depth breakdown, Jeff! Such a unique perspective, what with your having not yet seen the film - love it! Especially great observations about the directing on the page, too.